This summer, I was away from my home for seven weeks. My partner Chris and I used to do long trips every summer, taking advantage of our jobs on academic calendars. This was the first one since the pandemic began in early 2020. We were ambitious: spend 10 days in Paris during Chris’s conference, live in Provence for a month with a few short trips to nearby places, fly to Munich to see old friends, and make one more visit to Paris to witness Tour de France at Lille (an hour train ride from Paris).

The trip was pretty good. Even though I was not feeling my full self due to grieving over my grandmother’s recent passing, our lodgings were comfortable, and the historical sites and natural landscapes were impressive. Yet, something started nagging at the back of my neck in the middle of our trip. I began to visualize myself doing things in my American home: writing, making artwork, gardening, etc. We were backpacking with a minimal amount of luggage; as a result, I could only bring a few pens and pencils to work with. Also, I longed for my daily routines at home, which allow me to stay productive and achieve what I want to achieve each day. We had different schedules depending on the day’s excursion.

I tried to let go of an obsession with productivity and achievement and rather focus on what I can do. It was an effortful mental exercise for me since I was raised on the principle that working hard makes my life worthy. Relaxing got slightly easier over time, and my spare time journaling helped my recovery from grief. However, the nagging feeling did not go away but aggravated as we moved to Munich and back to Paris. I really missed home.

When Chris and I were working on our doctorate and master’s degree, respectively, we used to make a list of places we want to live after our graduation. Vancouver, BC was our first choice since it is beautifully surrounded by mountains and the ocean. We wanted to avoid the southern US, believing that I would experience more hatred as a queer Asian immigrant. Most of all, we wanted to leave the country and go to Europe or Asia. Trump was presiding as the president at that time, and any other country seemed to be better than the United States.

On my way back home, while waiting for our delayed flight at Charles-de-Gaulle airport, being seated with a KF94 mask in a fully-packed cabin, and later dutifully answering the questions of Customers and Border Protection officer, I fiercely wanted to get back to this country. There was nowhere else I would rather be than my home in Providence, Rhode Island. I even thought that from now on I won’t travel to any other country again and stick to domestic travels. What made my heart change? What happened to the adventurous Linda?

It could be just that I was away from home too long this time. After all, feeling homesick is a common experience for millions of people around the world. However, one thing I realized through this trip is that familiarity affects our experience greatly. My family immigrated to the US in 1998, and we lived through a high level of difficulty during the first ten years. Not only did we have to improve our English skills to a functioning level, but we had to learn how to operate in each step of our way. After 23 years of living here, I became familiar with the country inside out. I knew the average daily limit on withdrawal from ATM machines. I knew what kind of food I can procure at a chain pharmacy at a late hour after supermarkets are closed. I knew I will need to bring a long sleeve if I plan to ride a bus on a hot summer day because some drivers crank up that A/C to as cold as it can get.

Our home welcomed us with a box full of mail and packages. The people who subleased our place kindly collected them. Among the pile were seven issues of the New Yorker magazine, the oldest issue was from May 30th. I read the first article in The Talk of the Town, short updates from the last week of May. It was titled “Gun Country.” I learned more detailed information about Payton S. Gendron’s racially-motivated shooting in Buffalo, NY. I also found out more gun-related stats in the country such as 19,000+ “ghost guns” seized by the authority in 2021 (these guns are assembled without serial numbers, and therefore not tractable.) and some 45,000 deaths from gun-related wounds in 2020.

This is a not so welcoming prospect of life back at home, but at least I am familiar with the gun violence issues in the US. The overturn of Roe v. Wade was shocking but not surprising to me. Rampant violence, White supremacy, racism, misogyny, and the violation of human rights are all awful, but they have existed in this country as long as its history. This means that I can still operate within the system no matter how broken or corrupt. It also means that I know how to connect with people to organize and resist the system.

My maternal grandmother lived in a semi-basement of a multi-family building in Seoul for four years until she was sent to ICU and later moved to a facility for seniors who need assistance. There she shared a room with five other women, who would eventually die there as my grandma did. In her last home, she suffered from isolation, loneliness, and depression, in addition to various physical ailments. Still, she refused to move to a facility. My mother, her siblings, and even I tried to convince her thinking that she would feel less lonely among other elderly residents. But Grandma insisted that she stay at home because it is her own place. After my summer trip, I understand her a little more now.

P.S. I haven’t written a letter to you for a while. I haven’t been able to write much since my grandmother died in February. Meanwhile, I delved into visual art and explored drawing, collage, and watercolor. You can see them on my Instagram at KoreanLinda.

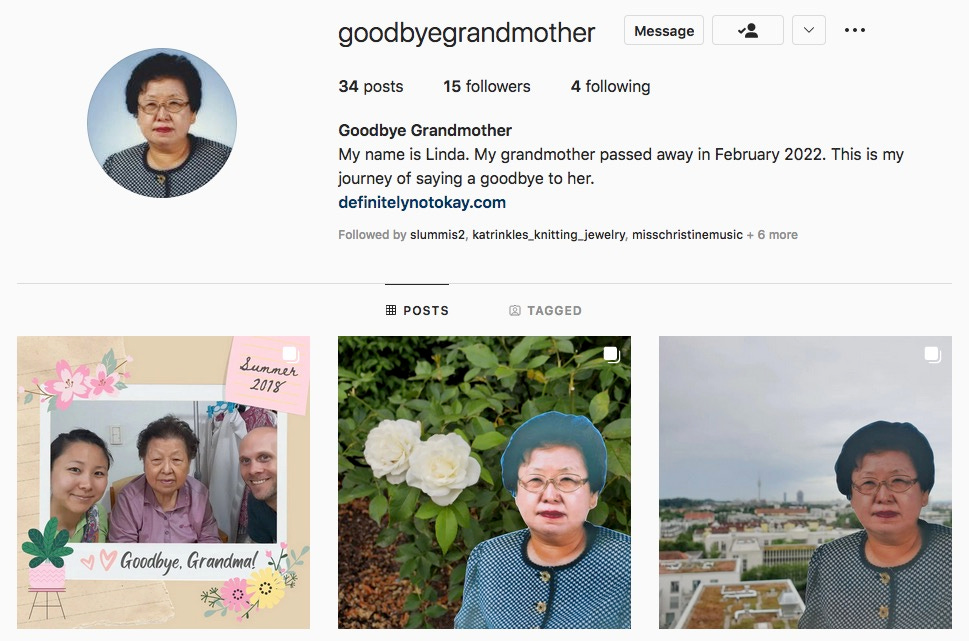

During my trip, I also ran a project called Goodbye Grandmother where I photographed places I visited holding up a cut-out of Grandma’s face. I accompanied it with journal entries, and this process helped me heal. You can see the project on Instagram at GoodbyeGrandmother.