Waiting in a Cage, Thinking of Home

Accounts of Asian Detainees on Angel Island Evoke My Painful Immigrant Memories

Lloyd Suh’s play The Far Country at Atlantic Theater Company was a rare treat I had craved. When I lived in New York City, I was comfortably immersed in the Asian American performing art scene. I could hear NYU Korean drumming group’s practices while strolling through Central Park. I frequented the plays and various shows put up by Asian American artists at Ma-Yi, La Mama ETC, The Public Theater, etc. The production photos of The Far Country emanated a sense of foreboding, but the story was personally appealing: the story of Asian immigrants.

Angel Island sounded innocuous or even positive. Through The Far Country, I learned that the small island in San Francisco Bay hosted detention barracks for immigrants who entered the country on the Wet Coast in the 19th century. Depending on their nationality, the duration of their stay varied widely as did their treatment. With the passing of the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882, countless people from China and other East Asian countries suffered detention with grueling interviews of unbearable length, ranging from several weeks to years.

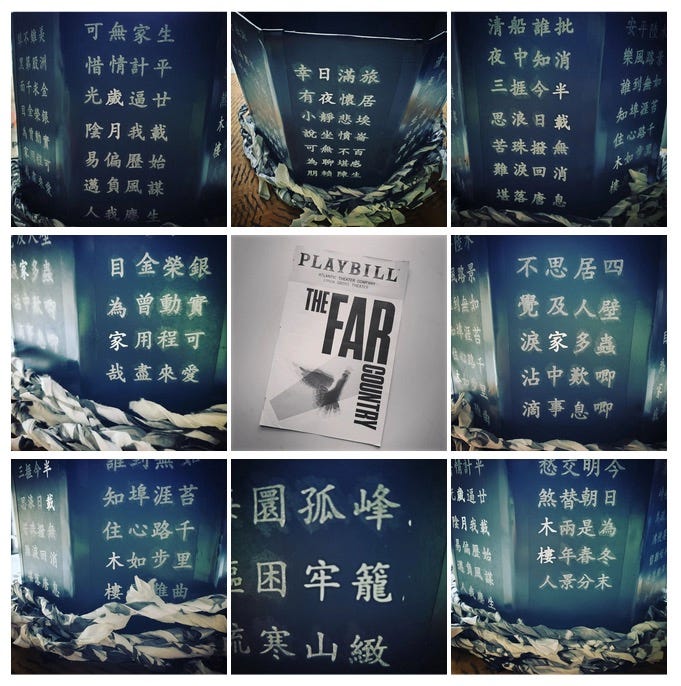

After the barracks stopped being used in 1946, it was reviewed for demolition to be replaced by a campground and recreational facilities. In 1970, a park ranger named Alexander Weiss discovered a multitude of Chinese carvings on the interior walls. Through the restoration efforts, hundreds of poems and inscriptions were found. While most were written in Chinese characters, English, Japanese, Russian, South Asian languages, European languages, and Korean were also represented.

I easily empathize with other’s pain, but the abuse of detainees I witnessed in the play hit me harder than usual. Memories of my encounters with U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) flew back to me. Once I was pulled aside at JFK airport and detained in a waiting room for an hour without explanation. Even nowadays reentering the US, I need to put all my ten fingers on the scanner one by one for the immigration officer to confirm that I am the person I claim to be. On the contrary, my US citizen partner passes through swiftly by showing a tiny photo of his face on the passport and waits for me at a distance. He makes sure he doesn’t lose sight of me. Eventually, I join him safely, and my eyes well up with tears of relief.

When I accompanied my parents for their citizenship interviews, the atmosphere of the office and the attitude of the staff couldn’t have been more clinical. It resembled a visit to a DMV office, but the mood was much more glum. At least at DMV, you get a waiting number and see the progress on a LED board. At USCIS, you just wait until your name is called. Having almost no control over your fate is the disturbingly normalized nature of US immigrants’ lives, and actors on the stage were playing it out so realistically that it gave me chills.

On our walk back to the train station, I told my partner Chris the story of my family’s immigration: how we made a decision to move here, how we encountered unexpected troubles on our flight to the US, how we were misunderstood at the customs check-point, and later on what my parents endured in order to maintain our visas and attain green cards.

I vividly remember one day in the winter of 1999. I was scrambling to get through all the steps to apply for college on my own. There was one college counselor at my public high school for the senior class of 600. I didn’t realize the inadequacy of the support I received for college admission until 15 years later when I worked for a private school in New Jersey where three college counselors guided 60 students.

Before the advent of online registration in the 21st century, I had to make a call in order to register for my first TOEFL (Test of English as a Foreign Language). It was at an unfamiliar location, so my mom drove me early in the morning and planned to wait outside for four hours while I took the test. It turned out I heard the date wrong when I registered so I missed my chance to take the test and wasted the $100 registration fee. (It was a large amount for us at the time. I gave up a youth group ski trip at my church because the cost was $100.)

Back at home, my mom got into bed and wailed all day. Our futile drive must have served as the last straw. She lamented the decision she and her husband made to immigrate to America, ending up in such a sorry plight. She was fed up with struggling every day to make a living in this linguistically hostile, racist country. The way she felt was not entirely my fault, but I nevertheless felt guilty for my inadequate English listening skills. The west-facing bedroom, tucked in a corner of a multi-family house, was dark from the lack of windows and cold from the lack of sunlight. I cried by my mother’s side, not knowing what to do.

***

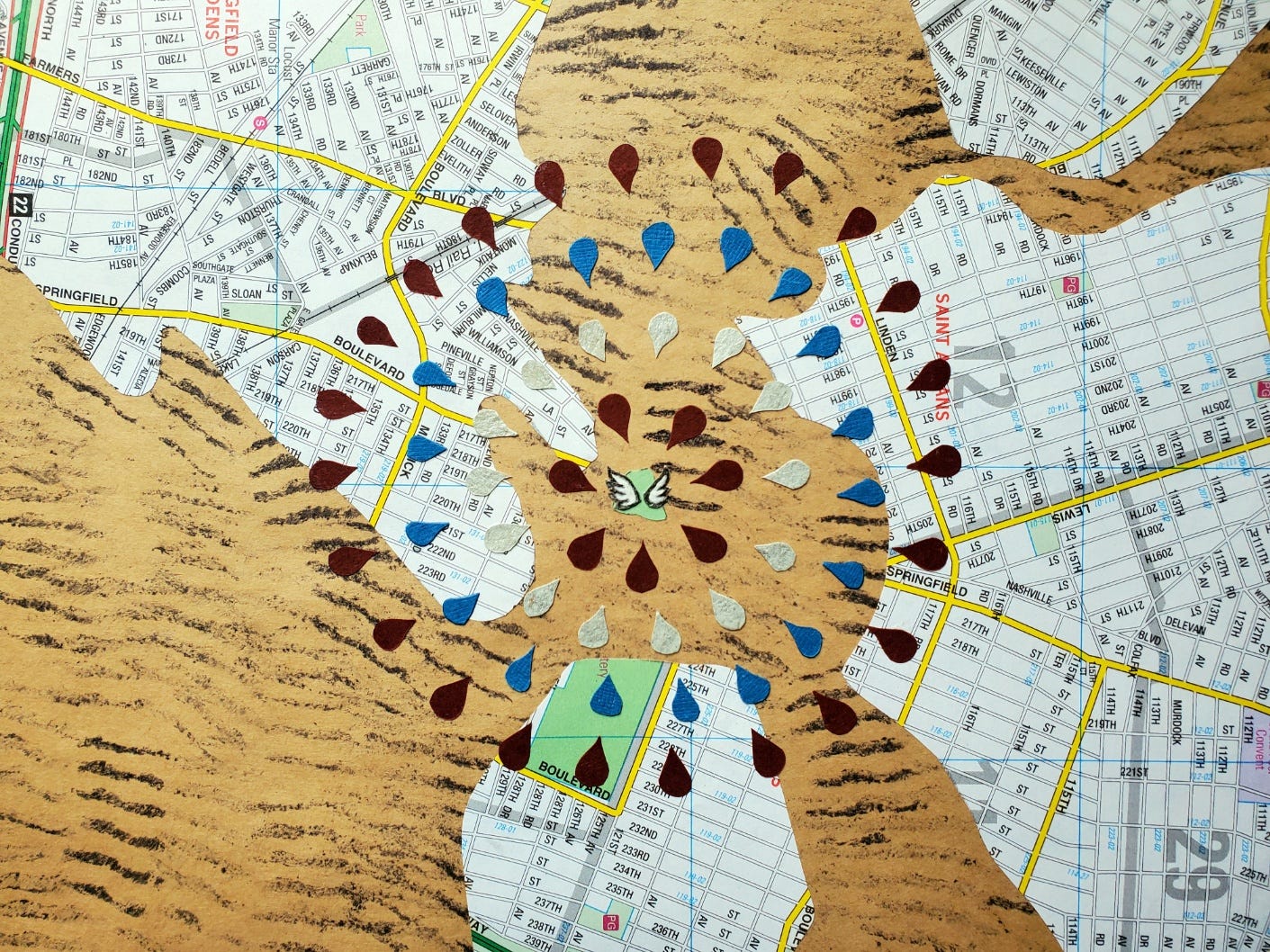

During the intermission of The Far Country, I saw copies of the Chinese wall poems displayed on the lobby tables for the audience to take. They traveled with me to Rhode Island and turned into a re-imagined barrack. As I read the poems, written in white against pitch-black backdrops, I found three recurring themes: home, building, and time. While waiting for the verdict on whether they could enter a new country, the detainees thought of their home country, felt helplessly trapped in a “cage,” and wondered how much longer they could last in such conditions.

No immigrant’s story is the same as any other, yet they are all connected. Leaving behind my whole life and entering new and unknown territory was scary, let alone a place that doesn’t welcome you. The stories of immigrants in Angel Island bleed with the pain they suffered; however, at the same time, the writing on the walls screams how resilient they were despite the level of hardship. Humans have been moving around the world pursuing survival and curiosity throughout their history. Attempting to stop the movement is against our nature; therefore ineffective and inhumane.

Listen to more stories of Linda and her buddy Heena on the American K-sisters podcast. Here is an episode about visiting Korea and returning to the United States. Never easy, is it?

Same episode recorded in Korean:

Thank you for sharing your story. 🫂💜