My Rare Disorder ITP Makes Me Even More Special

How the Common Enemy Revitalized My Will to Live

Content Warning: discussion of depression, suicide ideation, and death

For a long time, the biggest enemy in my life has been my chronic mental illnesses: namely depression and anxiety. Suicidal thoughts were by definition a direct threat to my existence. “To be or not to be” was a recurring question that constantly nagged my mind. It didn’t necessarily ask for an answer, but its mere existence created stress and weighed on my mood. Last month, an unexpected encounter with an “outer” enemy challenged the status quo: ITP, which stands for Immune Thrombocytopenic Purpura or Idiopathic Thrombocytopenia Purpura (signifying its unidentifiable cause).

My ITP was probably caused by a viral infection from a week before. I thought it was food poisoning because the symptoms started as soon as I left a restaurant with my family on a Sunday afternoon. I felt nauseous and dizzy. The world swirled around, and my body flipped inside out. I rushed into a Gong Cha cafe nearby and threw up in the restroom. The symptoms rotated through stomach pain, vomiting, dizziness, headache, body aches, and diarrhea for a week. Although I was feeling miserable, I firmly believed that it was food poisoning and self-treated my body with plenty of liquids, mild food, slow chewing, stomach meds, and rest. I also booked appointments with an acupuncturist and a chiropractor. I thought those should help relieve my various pain for sure.

A week after the onset, I noticed that something was off (more than usual sickness): red bloody spots under my skin (namely petechiae, I later learned). There were some on my chest and face. Maybe I scratched that area too much, I figured. I often run into furniture and get bruises on my legs. Seeing random marks on my body was a norm, not a concern. What scared me immediately was a small lump of blood I spit out during a shower. What the heck? It freaked me out. I inspected my mouth and found that the gums between two molars in the right corner were bleeding. That’s when I saw dark red, almost black, dots on my tongue. Hmm, I don’t remember biting my tongue today. My partner Chris urged me to see a doctor: “You have been sick for a week.” I finally gave in and called up my doctors: first the dentist, and the PCP. Then I tried to stop the bleeding with a cotton ball and an ice cube, and it worked! I’ll be fine, I repeated to myself.

The following day was quite hectic, trying to get to doctor’s appointments between my classes with no car. After getting confirmation from my dentist that my gums had no issues and drawing blood for various tests at my physician’s office, I was back home and settled knowing that I had done all I could do. I will see what comes out of the blood test when it does. In retrospect, it was a few hours of peace before everything got crazy, starting with a phone call from Morgan, the doctor on evening duty. Chris and I were sitting down to eat dinner: veggie stir-fry with rice. Chris had just arrived from a long day of teaching and had changed into his soccer kit to go to his weekly pickup games. Morgan delivered the news calmly. “Your platelet level is very low, less than 2,000. Go to an ER right now.” Despite their calm voice, my heart jolted. Chris and I acted promptly. Years of traveling in foreign countries and overcoming unexpected obstacles had trained us to stay calm and follow through on tasks. Chris looked up local hospitals in my network and found the best one in the state. He changed out of his soccer kit, and I changed into warmer clothes. I also packed snacks and drinks because I had barely touched my dinner plate and didn’t know how long we would be staying at the ER.

Although the subsequent days were eventful and even exciting to recount, I am going to skip to the day after my discharge.

. . .

As I started reflecting on my experience with the sudden unfamiliar symptoms and hospitalization, two moments came to my mind as the most memorable. The first moment was when I spit out blood during my shower, not knowing that it was from my gums. In my understanding, spitting out blood indicated that something was seriously wrong with you, and you were about to die (at least in the movies I had watched). I even said to Chris, “I didn’t want to die like this.” It was more about how than when. In my various scenarios of ending my life, bleeding to death was not an option. The petechiae and bruises that started appearing on my chest, face, and mouth reminded me of the photos of Atomic bomb victims in Hiroshima, and having a slow painful death from radiation exposure was not what I imagined for my demise, either.

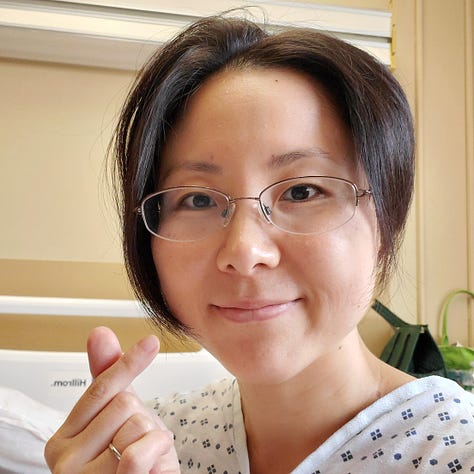

The second memorable moment was when I was sitting on my hospital bed in Room B414 with two visitors, Chris and my friend Devra. My right arm was hooked to the IV for a 4-hour long IVIg (Intravenous immunoglobulin) treatment. I was sleep-deprived from the late-night admission to the ER, numerous tests, and frequent vital checks. However, as I chatted with my visitors, I was elated. We were mostly making small talk because we didn’t have an interesting topic other than my current situation. Yet, in that moment, I sensed a strong desire to live. I was hopeful that I could continue living even if this scene became my daily life.

The source of hope for my prospects was not limited to these two visitors of mine. Constant interactions with medical staff and messages and calls with family and friends from afar kept me occupied and stimulated. Even though I was confined to a patient bed, I didn’t get much cabin fever thanks to these interactions and the consequent sense of connection to people.

Since I was admitted to the ER, what I had felt the most was relief and gratitude. I was glad I was not about to die soon, and I was grateful for having access to such high-quality medical care. In addition, I also felt hope and desire to continue. My brain focused on recovering from the present state so that I could continue to the next day. It was antithetical to suicidal thoughts. This whole experience revealed where I stand in my relationships with life and death. I wanted to accept both as what I am destined to experience as a living (dying) being.

I kept repeating this joke to friends that the universe thought my life was not challenging enough, so it decided to throw a wrench at it. (I live with chronic mental and physical illnesses, suffer from childhood trauma, grieve over my grandmother’s suicidal attempts and death, and work with high-need immigrant and refugee students.) Well, the wrench had already been thrown, and what I had control over was how I responded to it.

Common-enemy effect theorizes that “the interaction with a common enemy (in the form of Nature, an individual, or a group) makes individuals more prone to cooperate.” The sudden appearance of a wrench in my life in the form of ITP might have had that effect. All the cells in my body including the platelets under attack balled up together and braced themselves against the impact. They became one, chanting “We can do this! We can survive through this together!”

At the hospital, my medical team was efficient and effective in diagnosing my disorder and administering treatments. I left them a long thank you letter with a drawing of flowers, which Rudy the hematology unit secretary promised to post on the refrigerator in the staff lounge. He said he was sad to see me go because I was special. Not only did the medical staff make me feel special, but so did my disorder. Dr. Hsu, my appointed specialist said that my disorder, ITP, is so rare that if I would need financial support in case of a long-term treatment, there will be resources available to me. It would be an exaggeration if I said getting ITP made me lucky; however, it definitely made me (more) special.

Previous posts about other wrenches thrown at my life: